Lean Software Development

“But you are planning for failure!”

The planner on my project team was aghast. I had asked for components to cover a 3% predicted waste rate for a multi-year program making assemblies destined for orbit. As the manufacturing engineer for the program I knew from previous experience that 3% was an average, and not unreasonable, estimate of possible loss. This blog post attempts to answer whether her reaction was justified, but in the context of software development. Was she right to criticize my analysis of previous wastage of these components?

My background is in the aerospace engineering industry, specifically focusing on the manufacturing problems involved in hurling expensive hunks of metal into perpetual free fall around this blue orb. Despite all appearances, the space industry does not enjoy casually tossing away money. Instead, we stood on the sturdy foundations of Lean manufacturing, developed 60 years previously. As a software developer, a designer, or a program manager, how can we apply Lean Manufacturing to our programs, our processes, and our daily rituals?

What is Lean Manufacturing?

“Many people are busy trying to find better ways of doing things that should not have to be done at all. There is no progress in merely finding a better way to do a useless thing.” — Henry Ford

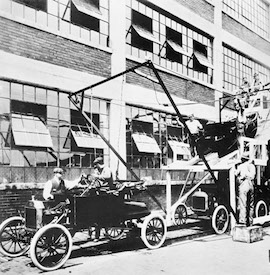

Lean Manufacturing has diverse roots. Benjamin Franklin can be credited with originating

Kiichiro Toyoda

some parts of it’s philosophy, and Henry Ford undoubtedly used and championed many of its principles, including reducing waste and optimizing ‘flow’. However, the first practical implementation of a series of standardized guidelines was developed by Kiichiro Toyoda at Toyota after the Second World War, and is known as the Toyota Production System (TPS). TPS is centered around systemized process improvement, waste reduction, and waste-cutting measures to only generate ‘direct value’, which is something a customer would directly pay for.

This application transformed the image of cars built by Toyota, and later, all goods manufactured by Japan, from something synonymous for junk into a product respected today and bearing a mark of high quality. In the 1980s, John Krafcik worked at Toyota and wrote an article titled: “Triumph of the Lean Production System”.

Detecting and eliminating waste in a system or process could be imagined as making it more efficient, thinner, or Leaner. Lean Manufacturing at its most basic is a toolset, and at its grandest is a philosophy.

Lean Coding

Applying this manufacturing mindset to coding is problematic for several reasons. The biggest difficulty in application at Grio is that each of our development problems is unique and requires varied resourcing, solutions, and creativity. Lean Manufacturing really shines when the same process, beginning with raw goods entering the factory and ending with a finished car rolling out, can be improved upon iteratively. The best way to apply Lean is to take a narrower approach. If we deconstruct Lean into its components, one principle stands out as being possible to apply to software development: waste reduction. The individual developer and designer can proactively improve their micro work-flow by reducing waste where it is found. Anyways, taking out the trash has always been the easiest chore.

Reducing waste in Lean Development

The original seven wastes of Lean Manufacturing are described briefly below:

Transport – Physically moving resources in a manner that does not contribute to the finished product

➡Inventory – All components and assemblies that are not currently being worked are using shelving space, and could even produce loss if they aren’t sold, or are damaged

Motion – People in motion that does not actively contribute to a finished product

➡Waiting – Waiting for the next production step

➡Overproduction – Production ahead of demand

Over Processing – Processing done on components that isn’t required by the consumer

➡Defects – Errors that must be corrected later

The arrows identify the wastes that have the most direct analogies in software development.

Inventory

Inventory is code that has already been written, and is waiting to be merged into the master code base. Inventory could be waste if it spends too much time in this state. It could fall far behind the code base and require extensive rebasing effort. Additionally, the work may be replicated in another task. The solution to this waste is tracking your open branches and moving to close tasks efficiently and sequentially.

Waiting

It’s easy to see waiting as a waste. Launching many processes to start up your dev environment takes time every day. If you can take half an hour at the beginning of the project to create a launch script, you’ll save hours over the length of a typical project. Next, instead of waiting for a full test suite to run to debug a single test, find ways to drill down and run only that single test. Better yet, use a package that watches your files and runs tests that apply to changed files.

Overproduction

This is a harder waste to identify. At the management/business level, this waste occurs when there is large effort put into a feature that doesn’t get used. At the developer level, we have to watch for replicating work being done by a co worker on a different branch. It is also possible that too much effort, or Over-Processing (see, I snuck a fifth waste in there) could be done on a feature that won’t see much use.

Defects

This is the easiest waste in software development to notice every day, but has been the bane of coders since time immemorial or at least since computers sprang into existence. The best way to try to reduce this waste is experience, code review, and extensive unit testing.

Lean Applied at Grio

Grio already uses agile methodologies extensively in the software lifecycle during our sprints. Sprints are short, iterative processes that have end products, and can be improved upon. Lean is just another agile methodology, with significant overlap. We have retrospective meetings at the conclusion of every other sprint to discuss how successful the last few weeks were, identify wastes, and improve our workflow. Sound familiar? At the conclusion of each project is a larger retrospective meeting that anyone at the company can join. These are great mediums for advancing company wide knowledge of all aspects of a project. At any software firm familiar with agile, you will find elements of classical Lean Manufacturing mixed in, as first idealized by Toyota.

Conclusion

I hope that this dubious method of applying car assembly methods to coding has resonated with you in some way. How can you improve your process in your job? The first step is in identifying where there is loss. After all, as Benjamin Franklin said, time spent not hammering away at your keyboard is time lost.

Now, back to the problem in the beginning of this post. Maybe you can guess the answer? A few months after the project moved from planning to production, it was discovered that one of the components I had over-ordered was machined from metal that hadn’t been heat-treated properly at the supplier. Hundreds of components had to be scrapped. This was a classic case of over production, and waste was generated despite my belief that I was planning ahead.