Atomic design: When a Button is a Molecule

If you’ve worked on a web design or development project, you can probably appreciate the benefits of reusing design elements across multiple website pages or app screens. Whether it’s a big, obvious chunk — a head or footer, say — or something much smaller, like an image or an icon, a design approach that allows for mixing and matching building blocks can save you a ton of time over one that’s constantly reinventing the wheel.

In 2013, designer Brad Frost coined a name for this building block-based methodology: Atomic Design. In this post, we’ll take a look at the definition and origins of atomic design, explain how it works, and discuss a few of its major advantages.

What is atomic design?

Atomic design is a design methodology that encourages breaking web pages and apps into smaller components, rather than looking at each page or screen as a unique design entity.

When Brad Frost formalized the atomic design methodology, his goal was to develop an approach that would make design more modular. Frost often heard colleagues and clients refer to designs at the level of pages or screens, but he noticed that they rarely discussed the individual elements that combined to create those larger layouts — and he realized that he lacked a good framework and terminology to bring the conversation down to the element level.

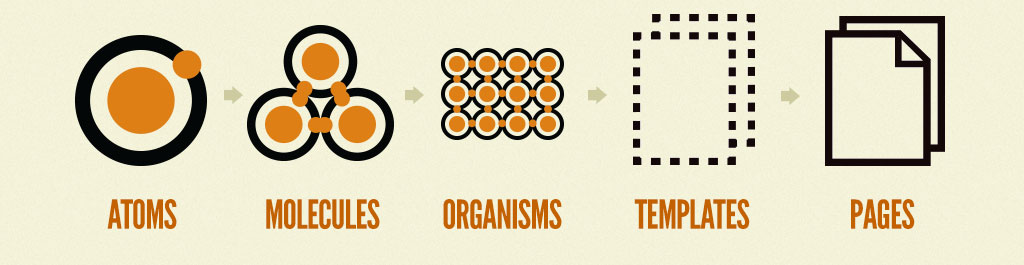

After doing some research on how other fields framed the concept of modularity, Frost settled on borrowing frameworks and vocabulary from the physical sciences. He called the smallest design elements “atoms”, and explained how atoms could be combined to form “molecules”, molecules to form “organisms”, and “organisms” to form templates and pages.

http://atomicdesign.bradfrost.com/chapter-2/

Since then, many companies have adopted Frost’s approach, and several have published their atomic design systems publicly. Google, for example, refers to their set of “atoms”, “molecules”, and “organisms” as the Material Design system. Salesforce’s Lightning Design System and Apple’s Human Interface Guidelines are other good examples.

How does atomic design work in practice?

Let’s take the example of designing a basic website. We’d start by creating “atoms” — icons, labels, images, etc. — and combining them into “molecules” like navigation menus and images with captions. Next, we’d use the atoms and molecules to create “organisms” — larger content blocks such as headers, footers, and interactive on-page elements — that we could use to construct wireframe templates.

Here atomic design breaks down all the elements of Instagram into atoms, molecules, organism, templates, and pages. http://atomicdesign.bradfrost.com/chapter-2/

Our final step would be to create at least one publication-ready page based on our templates. Creating a real page, with actual content, allows us to test the effectiveness of the underlying design system. Do all of the building block patterns hold up? Does everything look and function as it should? If not, we can loop all the way back to the atom stage and rebuild our molecules, organisms, and templates to better address our needs.

Why use atomic design?

The atomic design methodology offers a number of major benefits. Pulling from a library of reusable components results in:

- Faster prototyping — designers and developers are simply combining standard components, rather than building from scratch

- Easier updates and revisions — a component can be updated everywhere with a single change to its template code, and since components are designed to work together in various configurations, they can be swapped in and out with relative ease

- Improved consistency — using the same standard components in every instance reduces the need for constant cross-checking and eliminates many small errors

In addition to the above, an atomic design system can dramatically improve day to day communication among designers and developers. The system acts as a single source of truth, establishes a shared language, and gives teams a clear hierarchical framework that can be used to dissect and improve almost any template or page.

All that said, though, atomic design isn’t perfect. Like any system, it requires maintenance to function. Components need to be reviewed regularly, and updated so that they continue to hold up in implementation — and so that they reflect any ongoing shifts in the company’s overall design approach and visual brand.